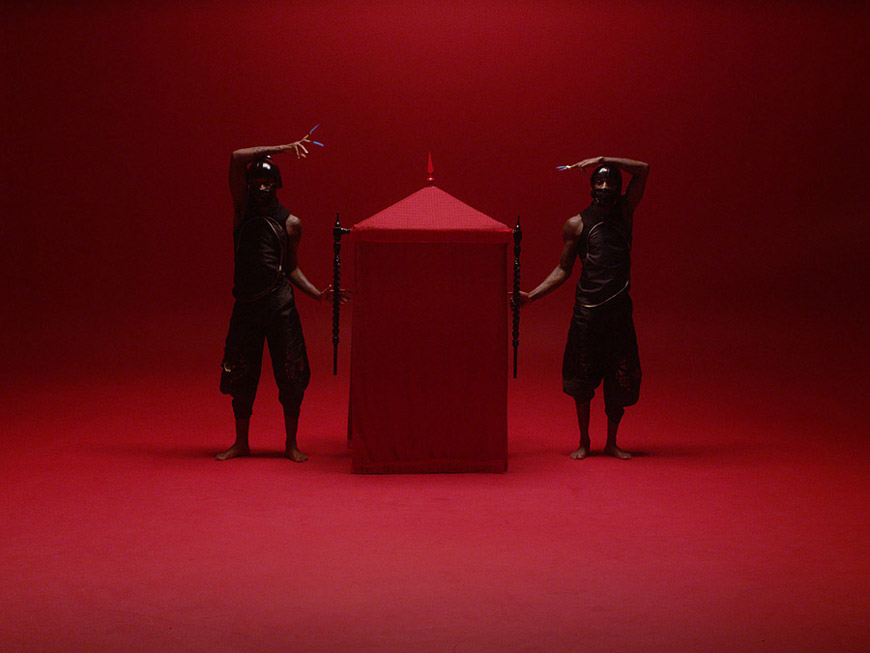

We recently featured the trailer for experimental artist and acclaimed filmmaker Andrew Thomas Huang’s latest project, Interstice. The mysterious work debuted as an art installation last month in New York, at Milk Gallery, featuring hellish digital paintings and a striking multichannel video. Today we’re excited to premiere the full online version of the film, which was inspired by the space between what is seen and what is obscured in traditional veiled lion dances.

The film features Flex artists Bones the Machine, Slicc, and Brixx, choreographed by Jason Akira Somma, with cinematography by Alexander Khudokon, production design by Lauren Nikrooz, and costume design by threeASFOUR. The original music is by CFCF. You can find the full production credits here.

In the lead up to the film’s release, Huang shared some insights about the deeply personal project, which is ultimately an investigation of his own cultural identity. Watch the full film above and read our interview with the Los Angeles-based director, below!

Jeff Hamada: When I watched Interstice it instantly reminded me of your short film from 2012, Solipsist; the sounds, and the dance ritual aspects felt somehow related. When I went back and read our interview from a couple years ago, you actually mentioned a darker sequel to Solipsist, is this it?

Andrew Thomas Huang: Yeah, I don’t know if I’d call it a sequel exactly but it’s definitely the follow up. After I finished Solipsist I knew whatever I made next had to serve as a counter to the soft, introspective, sandy, furry, colorful psychedelia that Solipsist was all about. This one had to be glossy, metallic, external and confrontational.

JH: The name suggests a small space or a moment in between. What exists on either side of this piece, the real world and the spiritual world?

ATH: When I was a kid I was really fascinated by lion dances, which I was exposed to when my family would go to Chinatown in LA to visit relatives on special occasions. Growing up I was told that the purpose of lion dances was to chase off demons. It really stuck with me, this idea that a lion dance was a method of channeling the spirit world and warding off evil. I guess the “interstitial” gap I’m referring to is this boundary between the dancer under the veil and the spirit world they are accessing on the other side of that fabric. Or perhaps on a broader level, the gap I’m referring to lies somewhere between my own ancestral heritage and the reality of my 21st century American present.

JH: What is your relationship to the veil?

ATH: In regards to lion dances, I’m less interested in the lion head itself than I am with the performer hiding beneath the cloth trailing behind the puppet. I always thought it was funny that you could see the legs of the dancer sticking out from beneath the cloth, yet the summation of the dancer’s movements created this uncanny, dislocated effect. A lion’s ability to chase off demons relies on this performer’s concealment behind a veil, allowing the dancer to become something greater than themselves.

I’ve often thought about the common saying that in a temple or church that the “veil is thin” between the physical world and the spirit world. Similarly, I wanted to make a film about that feeling of stepping into a charged space that was on the fringe of transformation: a space that is so overwhelming that it makes you dizzy. Like that feeling that you’re going to faint from a heightened state. I feel like horror movies are great at this. Whenever this radical upset happens I think of passing through a curtain or having a veil lifted so that I suddenly see something truthful that I didn’t really want to see.

I did some research and found some great essays about the veil and the history of its metaphoric use to amplify, exoticize and tease the promise of some hidden divinity. One article by Theodore Ziolkowski called “The Veil as Metaphor and as Myth” points out that it was Oscar Wilde who created the modern familiar image of a seductive veiled dancer with his “Dance of the Seven Veils” from his 1891 play Salome. This popular Western 19th century image of a veiled seductress is a common orientalizing trope that persists in western culture to this day.

Re-examining this oriental stereotype, it’s been impossible for me to think about the veil and not conjure other thoughts about cultural alienation and otherness. Again, the dualistic issue of self vs other is something I tend to get hung up on.

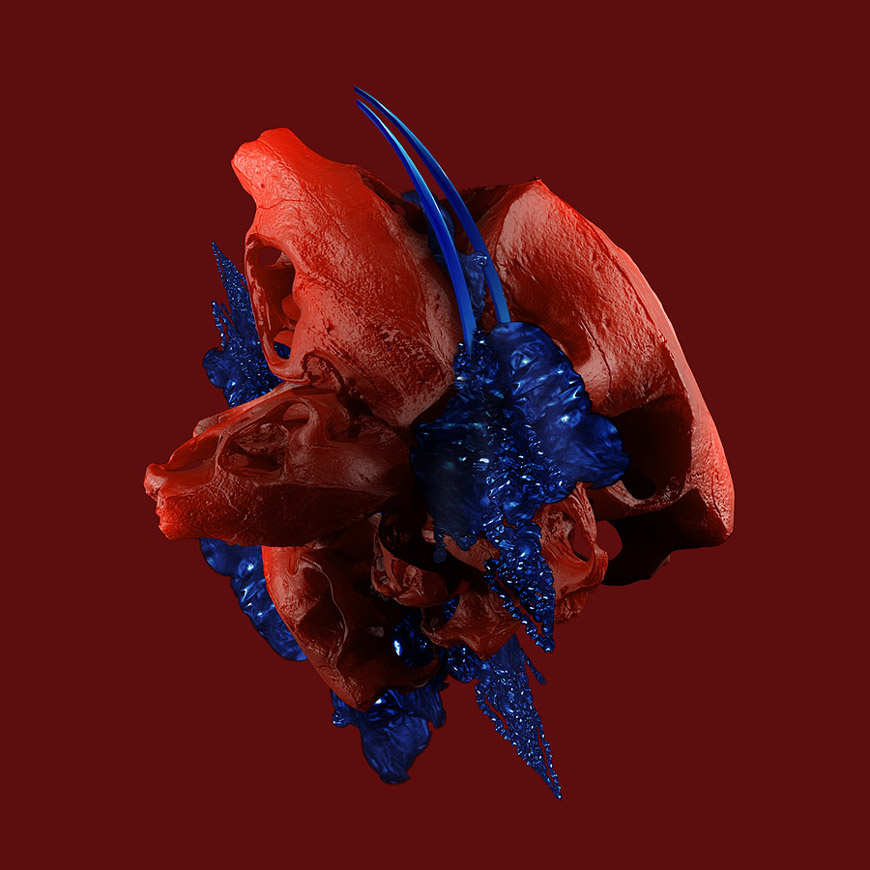

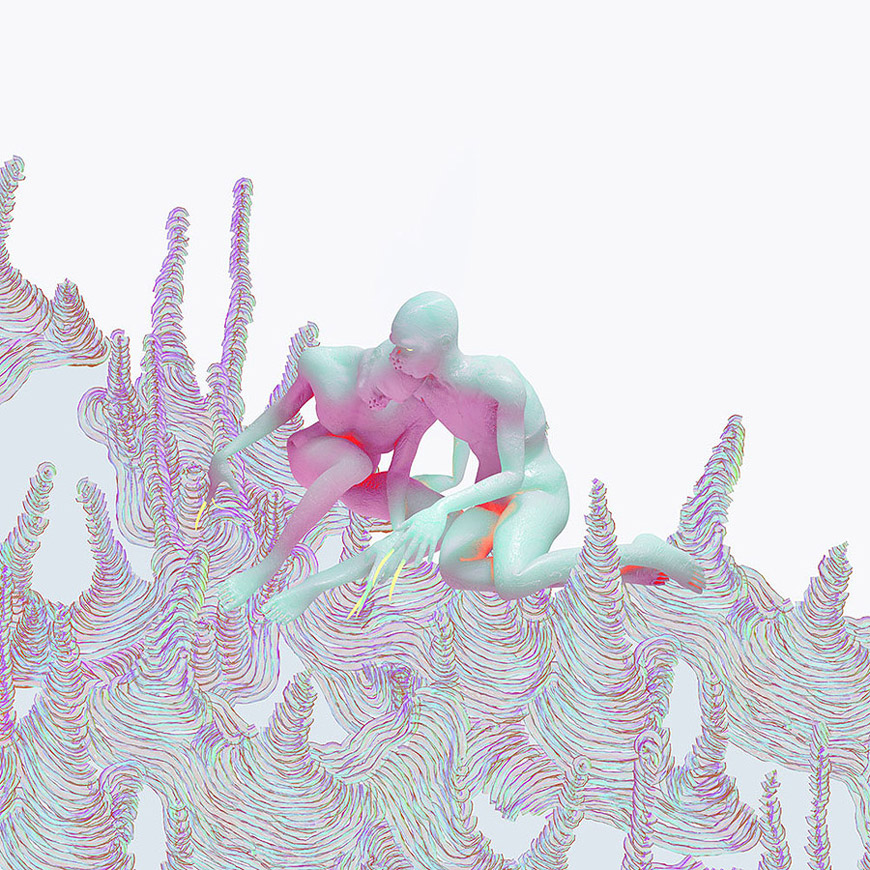

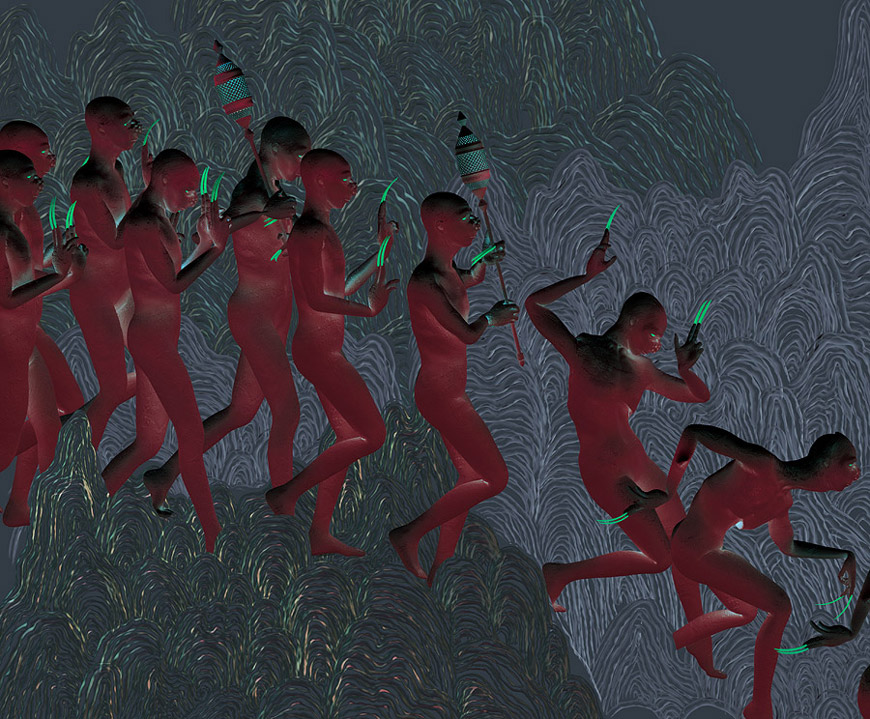

JH: Do the digital paintings that accompany the work come from a separate narrative?

ATH: The digital paintings are sort of an epilogue to the film. Alienation, conflict with orthodoxy, group exorcisms, divination rituals, origin myths and conceptions of “heaven” and “hell,” are definitely running themes. I was trying to create a sort of futuristic, digital 21st century Dante’s Inferno vibe with these.

JH: Can you share a bit of the process behind the paintings?

ATH: After finishing Interstice I was also coming off a 2 year period working on some really intense projects, so I was antsy to create work that I could just do alone on my computer at home. I wanted to figure out how I could tell sort of a larger mythic narrative without the challenges of animation or working with a large crew. I modeled the characters in Z brush, then rigged and posed them in Maya. Once I had a particular pose I could rotate and tumble around each character, relighting and rendering them from an infinite number of angles with various iridescent Mental Ray shaders to play up their glossy digital-ness. The backgrounds are also entirely digital, drawn by hand / wacom-tablet in Maya using Paint Effects to create each of the repetitive swirling patterns of the landscapes inspired by Chinese landscape painting. Once I rendered each figure and landscape element separately, I then collaged together these many layers within a flat, Medieval tapestry-like format in Photoshop.

JH: Is your approach any different for the creation of a film versus a multichannel art installation?

ATH: I approached the installation similar to the way I treat a film – building three acts, a bridge, climax, etc. However the installation has so many more variables and curatorial choices that need to be made. I wanted to make a spatial experience for Interstice because the film itself is about transforming space and it felt right to release the film in this immersive experiential way.

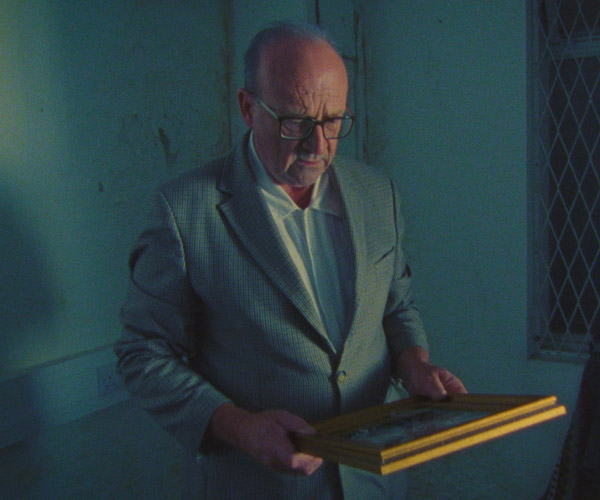

I tried to take advantage of the opportunities a gallery space offers. For instance, I took the metronome of the film, which is this golden lamp suggestive of a sort of orthodox fetish object, and brought it into the space where i could swing back and forth in the visitors’ space. This installation is both a kinetic sculpture that embodies the passing intervals between dual states, as well as a visual spectacle, not too dissimilar from swinging thuribles or censers used in orthodox churches.

ATH: Also for the show I was able to utilize an olfactory dimension. I worked with an amazing artist Stephen Dirkes who is a fragrance alchemist. My great grandmother and her family were apothecarists, so I wanted to fill the space with this visceral, bitter Chinese herbal scent. The installation definitely allows me to create a world that is much more immersive and visceral.

JH: I imagine making work to be shown in the MoCA or MoMA affords you a level of creative freedom that you might not have if you were making a film to be experienced in theatres. Does making a more traditional feature even interest you at this point?

ATH: Yea, absolutely. It’s kind of scary how many independent movies are made right now and how few are seen. But movies are my first love and are still to me one of the most democratized and accessible media to reach people. Movies are close to my heart and I’ve written my first draft of a feature that I hope to make very soon.

JH: What do you want people to take away from this work?

ATH: I guess I’m trying to share with people that uneasy feeling of in-betweenness. I want to show them something that’s seductive and beautiful but ends with a sobering wake up call – like a veiled knife. When I was making the film, I was thinking about crimson and gold lion dances as lasting symbols of my heritage. As an American I have no real ownership over these aspects of my heritage, and nostalgia for my ancestry runs the risk of romanticizing it. I think it’s dangerous to orientalize and exoticize one’s past, but how is it possible to avoid this as someone culturally displaced? How is it possible for us who are culturally displaced to dispel the illusions projected onto us? It’s so difficult to see past ourselves. These are the questions I hope people come away with.

Andrew Thomas Huang on Facebook

Andrew Thomas Huang on Twitter

Andrew Thomas Huang on Instagram

Share

Share

Tweet

Tweet

Email

Email